- Home

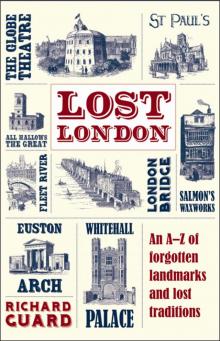

- Richard Guard

Lost London Page 3

Lost London Read online

Page 3

His illustrated furniture catalogue made him famous around the world and both Louis XIV and Catherine the Great were known to own copies.

Not only a designer of furniture, Chippendale also made wallpaper, brassware and carpets, and his illustrious clients included the architect Robert Adam, the actor David Garrick, the outrageous Mrs Cornelys (Chippendale was one of her creditors when she was imprisoned for debt) and Lord Mansfield, who installed Chippendale’s work at his Kenwood House home in Hampstead. Similarly, Lord Shelbourne bought furniture for his Lansdowne House property in Berkeley Square.

On Chippendale’s death in 1779, the business passed to his sons but tastes were changing. In 1793 Chippendale’s work was described as ‘wholly antiquated and laid aside’. In 1804 the business failed and all the company’s remaining stock was auctioned. ‘Beautiful Mahogany Cabinet Work of the first class, including many articles of great taste and the finest workmanship’ were sold off in under two days.

Clare Market

Aldwych

BUILT IN AN AREA PREVIOUSLY KNOWN AS ST Clement’s Inn Fields, Clare Market was established in 1651 on land owned by Lord Clare, whose family home – ‘a princely mansion’ – once stood here.

The market was held every Wednesday and Saturday and became famous for its meat and fish. By 1850, more than twenty-five butchers were slaughtering almost 400 sheep and 200 bullocks a week. However, the gradual encroachment of slum dwellings saw the market’s reputation decline. Writing in 1881, Walter Thornbury noted that ‘merchandise at present exposed for sale ... consists principally of dried fish, inferior vegetables, and such humble viands, suited to the pockets of the poor inhabitants of the narrow courts and alleys around’.

The market was not to survive many more years. Much of the land on which it stood was used for the building of the Royal Courts of Justice. Today, its name is remembered in a meagre passageway on the campus of the London School of Economics.

Coldbath Fields Prison

Clerkenwell

BUILT IN 1794 ON THE SITE OF A COLD spring discovered in 1697, this prison was notorious for the severity of its regime.

It was immortalized by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who wrote:

As he went through Coldbath Fields he saw a solitary cell:

And the Devil was pleased, for it gave him a hint

For improving his prisons in Hell.

The first prison governor, Thomas Aris, allowed inmates one visitor and one letter every three months. Hopes that the next governor might oversee an improvement in conditions were dashed when Aris was replaced by a military man with even harsher views. Under the guidance of George Chesterton from 1828, the prison population doubled to 1150. Many were short-term prisoners, and 10,000 petty thieves, drunks and vagrants passed through its walls every year. Chesterton did root out corruption in his staff by placing spies among them, but he also imposed a vicious regime on the prisoners, including total silence. Protesters were flogged, placed in solitary confinement wearing leg irons, and fed bread and water.

Perhaps the jail’s most famous inmates were the Cato Street conspirators (led by Arthur Thistlewood), who were subsequently moved to the Tower of London before being hanged at Newgate. Coldbath Fields was closed in 1877 and demolished in 1889, the site later becoming the home of the Mount Pleasant sorting office.

Colosseum

Regent’s Park

A VAST ROTUNDA BUILT IN REGENT’S PARK BY Decimus Burton between 1824 and 1827, with a dome very slightly larger than that of St Paul’s Cathedral.

It housed a huge canvas panorama of London, painted by Thomas Hornor. However, the attraction’s initial popularity soon waned and in 1831 the building was sold to opera singer John Barham, whose dream to turn it into an opera house took both his fortune and his health. Briefly used for magic-lantern shows, the Colosseum was demolished in 1872 and is now covered by Cambridge Gate.

Costermongers’ Language

Today’s street slang and text-speak can trace their roots back to the Victorian costermongers (street traders) who developed a language of their own. Their motives were very similar to those of the slang-merchants of today – to mark themselves out as separate and special, and to avoid being understood by the authorities. As one costermonger was reported as saying:

The Irish can’t tumble it anyhow; the Jews can tumble it better ... Some of the young salesmen of Billingsgate can understand us – but only at Billingsgate, and they think they are uncommon clever, but they’re not quite up to the mark. The police don’t understand us at all. It would be a pity if they did.

Here are a few favourite costermonger phrases:

A doogheno or badheno?

Is it a good or bad market?

A regular trosseno

A regular bad one

Cool him

Look at him

Cross chap

A thief

Do the tightner

Going to dinner

Doing dab

Doing badly

Flash it

Show it

Flatch kanurd

Half-drunk

I’m on to the deb

Going to bed

Kennetseeno

Sticking

Nomus

Do off

Tumble to your barrkin

Understand you

Crapper and Company Ltd

Chelsea

THOMAS CRAPPER WAS SUBJECT TO AN ENDURING myth that he lent his name to a popular slang verb (the word crap derives from the Dutch krappe),

Thomas Crapper was a plumber who ran a very successful business (on the King’s Road in Chelsea) making celebrated water closets between 1861 and the late 1920s. Crapper’s former premises at 120 King’s Road became the site the of Dorothy Perkins store.

Cremorne Gardens

Chelsea

A 12-ACRE SITE BETWEEN THE KING’S ROAD AND the River Thames, Cremorne was a Victorian revival of an earlier pleasure gardens.

It was originally opened as Cremorne Stadium in 1832 by Charles Random de Berenger, who styled himself Baron de Beaufain or Baron de Berenger (depending on how the mood took him). His aristocratic heritage was entirely fictitious and he had in fact only recently been released from King’s Bench Prison for stockmarket fraud.

Promising ‘manly exercise’ including boxing, swimming, fencing, rowing and shooting, the venture was not the success that the ‘Baron’ had hoped. Having changed hands, it reopened in 1840 as a pleasure garden, complete with banqueting hall, theatre, bowling, grottoes and lavender bowers, and enough space to accommodate 1,500 people.

With a grand entrance on King’s Road, the entry fee of one shilling permitted guests fifteen hours of entertainment, including fireworks shows, circuses and side shows. But Cremorne’s speciality was balloon ascents, which became increasingly daring and dangerous and thoroughly captured the public imagination. One exponent, Charles Green, memorably made one flight in the company of a leopard. Another, ‘The Flying Man’ Goddard, rose to 5,000ft in his Montgolfier Fire Balloon in 1864, before drifting into the spire of St Luke’s Church on nearby Sydney Street with fatal results.

By the 1870s Cremorne Gardens had acquired a poor reputation and the local Baptist minister issued a pamphlet calling it a ‘nursery of every kind of vice’. Despite successfully suing for libel, the owner, John Baum, was awarded only a farthing in damages. Ruined both in health and pocket, Baum’s licence was withdrawn in 1877. Lots Road power station later came to cover much of the site.

Crossing Sweepers

IN HENRY MAYHEW’S London Labour and the London Poor, published in several volumes from 1851, the author lists all the strange, sad, hideous and downright bizarre jobs that London’s Victorian poor were driven to in order to eke out a living.

He gives over almost thirty pages to the now defunct work of the crossing sweeper; who kept busy street crossings free from rubbish and horse dung in the hope of eliciting a few pence from those traversing the highway.

/> Many turned to this business as its start-up costs were minimal – one merely needed a broom. It provided a job that meant the sweeper would avoid being charged with begging, and if they could establish a regular pitch, they might earn the sympathy of local householders and shopkeepers and begin to make a regular income from them.

Mayhew lists a number of banks and businesses that employed crossing sweepers to keep their customers’ feet clean en route to their premises. He interviewed many of them and categorized them thus:

Able-bodied Crossing Sweepers

The Aristocratic Crossing Sweeper

The Bearded Crossing Sweeper at the Exchange

The Sweeper in Portland Square

A Regent Street Crossing Sweeper

A Tradesman Crossing Sweeper

An Old Woman

The Crossing Sweeper who had been a Serving Maid

The Sunday Crossing Sweeper

One-Legged Crossing Sweeper of Chancery Lane

The Most Severely Inflicted of all the Crossing Sweepers

The Negro Crossing Sweeper who has lost both his legs

Boy Crossing Sweepers

Gander The ‘Captain’ of the Crossing Sweepers

The King of the Tumbler Boy Crossing Sweepers

(And finally) The Girl Crossing Sweeper sent out by her Father.

The Devil Public House

Fleet Streeet

A PUBLIC HOUSE, DATING BACK TO THE 16TH century, whose sign depicted St Dunstan tweaking the nose of the devil, was the site of the Apollo Club, home to wits, writers and poets presided over by the playwright, Ben Jonson.

The rules of the club, most likely written by Jonson himself, stated:

Let none but guests or clubbers hither come;

Let dunces, fools, and sordid men keep home;

Let learned, civil, merry men b’ invited,

And modest, too; nor be choice liquor slighted.

Let nothing in the treat offend the guest:

More for delight than cost prepare the feast.

Other rules forbade reciting insipid poetry, fighting, brawling, itinerate fiddlers, the discussion of serious or sacred subjects, the breaking of glass or windows, and the tearing down of tapestries in wantonness (presumably tearing them down with good reason was excusable).

During Cromwell’s Commonwealth, the Devil became the favourite roost of ‘Mull Sack’ – so named because his chosen drink was spiced sherry. Mull Sack’s real name was John Cottington, a sweep turned highwayman and cutpurse, who reputedly had stolen from both the Lord Protector Cromwell and Charles II and who was immortalized in popular ballads of the time.

In 1746 the Royal Society held its annual dinner here and during the 1750s concerts were regularly hosted. Eventually the Devil was incorporated into Child’s Bank, which stands at No 1 Fleet Street.

Dioramas

A FASHIONABLE DIVERSION AND FORERUNNER OF the cinema, the first diorama opened in 1781 at Lisle Street. Described by its inventor, Philippe de Loutherbough, as ‘Various imitations of Natural Phenomena represented by Moving Pictures’, it consisted of a series of mechanically operated scenes, such as a storm at sea.

The most famous diorama opened in 1823 at Nos 9–10 Park Square East, Camden. In a darkened auditorium, 200 seated visitors were treated to a series of vast trompe l’oeils painted by Jacques Daguerre, inventor of the first successful photographic technique. The entire seating could be rotated through nearly ninety degrees by a boy operating a ram engine, allowing parts of a scene to be displayed while other parts were prepared off-stage and out of sight. Measuring seventy feet wide and forty feet high, the giant paintings included the interior of Canterbury Cathedral. One visitor described the experience of seeing the former thus: ‘The organ peels from under some distant vaults. Then the daylight slowly returns, the congregation disperses, the candles are extinguished and the church with its chairs appears as at the beginning. This was magic.’

Although hailed as an artistic triumph, the venture was a commercial failure and in 1848 the building, its machinery and paintings were sold for £3000. The site was later converted into a Baptist chapel, though the original frontage survives.

The Dog and Duck

Southwark

A FAMOUS PUBLIC HOUSE, NAMED AFTER EITHER the shape of the nearby ponds or the habit of allowing dogs to chase the ducks that lived on them.

The pub gained a reputation not only for its sporting contests but also for its health-giving waters. Sold at 4d a gallon and recommended by no less a figure than Dr Johnson to his friend Mrs Thrale, the waters were advertised in 1731 as being a cure for ‘rheumatism, stone, gravel, fistula, ulcers, cancers, eye sores, and in all kinds of scorbutic cases whatever, and the restoring of lost appetite’.

If healthy competition was more your thing, in 1711 the pub hosted a ‘grinning match’ in which contestants, to the accompaniment of music, competed for a gold-laced hat. The Dog and Duck was much enlarged over time to include a bowling alley and an organ for popular concerts. But in contrast to the nearby Vauxhall Gardens, it gained a poor reputation, attracting as it did ‘riff-raff and the scum of the town’.

Numerous highwaymen of the 18th century made mention of the pub and in 1787 it was refused a licence until the Mayor of Southwark intervened. It was again refused one in 1796, at which stage it changed from a public house into a vintners, which needed no licence to operate. It closed down altogether three years later. With the pub demolished, the site became home to St Bethlehem when it moved from Moorfield in 1811. A stone plaque from the Dog and Duck, portraying a sitting dog with a duck in its mouth and bearing the date 1617, was incorporated into its walls but was later moved to the Cuming Museum in Lambeth.

Dog Finders

ONE METHOD THAT SOME POOR LONDONERS used to earn money was the trick of ‘lurking’ or dog finding.

Henry Mayhew interviewed one dog finder for his great work on London, a man named Chelsea George who had been educated as a gentlemen but had fallen on hard times.

Chelsea George had a cunning technique. He would paint his hand with gelatine mixed with pulverized fried liver and then approach a dog that looked ‘a likely spec’. Rubbing his hand on the animal’s nose, it soon became a willing captive. He would abduct the animal with a sack he carried for the purpose, then have flyers printed declaring ‘Dog Found’. He posted one at a local public house with a friendly landlord and the other he kept on his person.

When the dog’s owner approached the publican, they were directed to George, who would produce the other flyer – saying he had come across it during the day – and return the dog for a reward. Mayhew believed Chelsea George had run this trick for nearly fifteen years ‘without the slightest imputation on his character’, earning him an annual income of around £150 (which in Victorian London put him on a par with a headmaster, and way above a labourer who could expect £25 per year).

Don Saltero’s Coffee House

Chelsea

A CHELSEA INSTITUTION FOR ALMOST 150 YEARS, Don Saltero’s was opened in 1695 by one James Salter, a barber and former servant of Sir Hans Sloane.

Originally on the corner of Lawrence Street, it moved first to Danvers Street and then in 1717 to Cheyne Walk This popular coffee house was packed with curiosities donated by Sloane, whose collection of objects would later form the basis of the British Museum.

Salter acquired his ‘Don’ nickname from Rear-Admiral Sir John Munden, a notorious lover of all things Spanish. Salter was an eccentric, not only serving his customers coffee but also shaving them, pulling their teeth, reciting poetry and playing the violin. His fame reached its apogee in 1709 when an edition of the Tatler was dedicated to his shop and its ‘ten thousand gimcracks’.

After Salter’s death in 1728, the business passed to his daughter. A year later a catalogue of the items in the coffee house was published, and again in 1795. A good many of them were sold off in 1799, raising £50 despite (or perhaps because of) including ‘a starved cat found betwe

en the walls of Westminster Abbey when repairing’. No 18 Cheyne Walk, built in 1867, now sits on the site.

Durham House

The Strand

FOR 800 YEARS BEFORE THE EMBANKMENT WAS built, the Strand was the site of many of London’s finest houses, offering both river views and close proximity to the City and Westminster.

Durham House was originally built in the mid-14th century as the town house of the Bishop of Durham. The first officeholder to reside there was Richard Le Poor. Legend has it that Henry III was once passing nearby during a thunderstorm when the then incumbent, Simon de Montfort, invited him in to take refuge. The king replied, ‘Thunder and lightning I fear much, but by the head of God I fear thee more’.

The house also served as home to both Cardinal Wolsey and Anne Boleyn, while Katherine of Aragon lodged here before her marriage to Henry VIII’s older brother, Arthur. Lady Jane Grey was wed here on 21 May 1553, shortly before her tragic nine days on the throne of England. By the time of Elizabeth I’s reign, the house was described as ‘stately and high, supported with lofty marble pillars. It standeth on the Thames very pleasantly.’ It eventually became the home of Sir Walter Raleigh and while living there he was memorably drenched with beer by a servant who feared that his master had caught fire when he found him smoking.

Lost London

Lost London