- Home

- Richard Guard

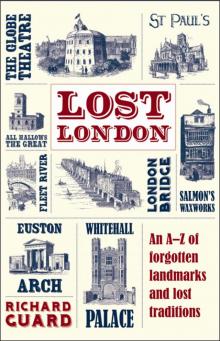

Lost London

Lost London Read online

For Kirsty, Oliver, Isaac and Alfred

Seized by a compulsion you long to discover Drayton Park.

Go there at once and miss a turn. The London Game, Seven Towns Ltd, 1972

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

Michael O’Mara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright © Michael O’Mara Books Limited 2012

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84317-803-3 in paperback print format

ISBN: 978-1-84317-896-5 in EPub format

ISBN: 978-1-84317-895-8 in Mobipocket format

Designed and typeset by Design 23

Picture research by Judith Palmer.

Jacket picture sources: Antiquities of London and Its Environs, Antiquities of Westminster, both by John Thomas Smith; Father Thames by Walter Higgins; London by Walter Besant; Knight’s London, Vols. I, V, VI; The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Vols. XII & XIX; Old and New London, Vols. I, II, VI, by Walter Thornbury and Edward Walford; The Old Bailey and Newgate by Charles Gordon; A Short History of the English People, Vol. II, by J. R. Green. Page 24 www.clipart.com

www.mombooks.com

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Ackerman’s The Strand

Adam and Eve Tea Gardens Tottenham Court Road

Agar Town King’s Cross

Alhambra Leicester Square

Alsatia Temple

Archery

Astley’s Westminster Bridge Road

Atmospheric Railway Southwark

Barbican EC2

Bartholomew Fair Smithfield

Baynard’s Castle Blackfriars

Bedlam, or St Bethlehem’s Hospital Liverpool Street

Bishopsgate

Bon Marché Brixton

Bridewell Banks of River Fleet

Carlisle House Soho Square

Charing Cross

Chelsea Bun House

Chippendale’s Workshop Covent Garden

Clare Market Aldwych

Coldbath Fields Prison Clerkenwell

Colosseum Regent’s Park

Costermongers’ Language

Crapper and Company Ltd Chelsea

Cremorne Gardens Chelsea

Crossing Sweepers

The Devil Public House Fleet Street

Dioramas

The Dog and Duck Southwark

Dog Finders

Don Saltero’s Coffee House Chelsea

Durham House The Strand

Eel Pie House Highbury

Effra River South London

Egyptian Hall Piccadilly

Enon Chapel Near the Strand

Essex House Near the Strand

Euston Arch

Execution Dock Wapping

Exeter House The Strand

Farringdon Market

Fauconberg House Soho

Field of the Forty Footsteps Russell Square

Fleet Marriages

Fleet Prison Blackfriars

Fleet River

Frost Fairs

Gaiety Theatre The Strand

Gamages High Holburn

Gentleman’s Magazine

The Globe Bankside

Goodman’s Fields Theatre Whitechapel

Gore House Kensington

The Great Globe Leicester Square

Gunter’s Tea Shop Mayfair

Hanover Square Rooms

Harringay Stadium

Highbury Barn

Hippodrome Racecourse Ladbroke Grove

Hockley-in-the-Hole Clerkenwell

Holborn Restaurant

Holy Trinity Minories Tower Hill

Horn Fair Charlton

Islington Spa, Or The New Tunbridge Wells

Jacob’s Island Bermondsey

Jenny’s Whim Pimlico

Jonathan’s Coffee House Bank

Kilburn Wells

King’s Bench Prison Borough

King’s Wardrobe Blackfriars

Kingsway Theatre Holborn

Leicester House Soho

Lillie Bridge Grounds Earl’s Court

Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre

London Bridge Some Notable Decapitated Heads Displayed Thereon

London Bridge Waterworks

London Salvage Corps

Lowther Arcade The Strand

Lyons Corner Houses

Molly Houses

Mudlarks

Necropolis Railway Waterloo

Newgate Prison Old Bailey

New River Head Clerkenwell

Nine Elms Railway Station

Nonsuch House London Bridge

Old Clothes Exchange Houndsditch

Old Slaughter’s Coffee House Covent Garden

Pantheon Oxford Street

Paris Gardens Bankside

Patterers, or Death Hunters

Penny Gaffs

Peerless Pool Shoreditch

Pillory

Plague Pits

Pure Collectors

Queen’s Hall Langham Place

Rainbow Coffee House Fleet Street

Ranelagh Gardens Chelsea

Ratcliffe Highway Wapping

Rillington Place Ladbroke Grove

Rivers

The Rookeries

Rosemary Lane Tower Hill

St George’s Fields Southwark

St Paul’s Cathedral

Salmon’s Waxworks Fleet Street

Silvertown Explosives Factory West Ham

Slang

Steelyard Cannon Street

Street Cries

Street Traders

Tabard Inn Borough

Thorney Island Westminster

Toshers

Tyburn Marble Arch

Vauxhall Gardens Lambeth

Walbrook

Watermen

Whitehall Palace Westminster

Wren’s Lost Churches

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

London is a very old and magnificent city – but its buildings are not that ancient. Although it has been inhabited for 2000 years few traces are left from that time. Tiny sections of the old wall and the London Stone from which the Romans measured distances throughout the land are all that remain. Mosaics, foundations and artefacts have been frequently uncovered, but there’s no colosseum, amphitheatre or Parthenon to mark 400 years of Roman rule.

The medieval period too has little to show for itself – a few churches claim to have been established in the 10th century, but the oldest existing building is William the Conqueror’s White Tower, the original Tower of London, built in 1085.

A series of rapid expansions and terrible disasters have stripped the capital of its age old monuments. Most famous is the Great Fire of 1666 which destroyed 90 per cent of the old city. Over ten thousand new dwellings were built in its aftermath – none are left – the German Blitz destroyed the last of these.

Much of the city built between the Great Fire and the death of Queen Victoria in 1901 – the city immortalized in the works of Charles Dickens – was swept away with modernizing and moralizing zeal. Massive urban development consumed the fields where city dwellers once took their pleasures. The railways sliced through ancient thoroughfares and demolished districts tha

t had stood for hundreds of years. Many fabulous and remarkable buildings were simply removed because they were old.

Now only a few glorious pockets of 18th century London remain. It would be a fool’s errand to attempt to describe all that has been lost – indeed it would be impossible. This humble book only aims to amuse its readers by describing some of the buildings and streets, the jobs and habits, the markets, fairs and pastimes that have made London what it is today, the greatest city in the world.

London has been the epicentre of so many important historical events – in politics, in the arts, in science – that for lovers of the capital the very streets seem to reverberate with echo of voices past. In compiling this book I have attempted, where possible, to find a contemporaneous quote that brings the location and the time and place back to life, so that the reader will be able to walk the city’s streets and people them with the great rush of humanity that have called London their home for the last 2000 years.

RG, EAST DULWICH, 2012

Ackerman’s

The Strand

OPENED BY RUDOLPH ACKERMAN, AN Anglo-German bookseller and print-maker, this shop was not only the first art library in England but also the first to be lit by gas ‘which burns with a purity and brilliance unattainable by any other mode of illumination’.

The building had been an art school from 1750 until 1806, attended by such notable figures as William Blake, Richard Cosway and Francis Wheatley. Beginning in 1813, Ackerman held soirées each Wednesday attended by the great and good, many of whom were attracted by the fact that he was a prominent employer of aristocrats and priests who had fled the French Revolution. As well as selling books, prints, fancy goods and artists’ materials, it was for many years the ‘meeting place of the best social life in London’.

Ackerman was also a notable publisher. Each month from 1809 to 1828, he printed The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce and Manufactures, a major historical source of information on Regency fashion and a treasure trove for modern makers of Jane Austen period dramas. Meanwhile, his The Microcosm of London, or London in Miniature (1808–1810) contains hand-coloured aquatints of many since-lost city views. Ackerman’s publishing business ended in 1858 and the site of his shop is now home to the legendary restaurant, Simpson’s-in-the-Strand.

Adam and Eve Tea Gardens

Tottenham Court Road

FROM 1628 UNTIL THE LATE 1700s, CITY DWELLERS tired of the hustle and bustle of life could take a stroll to this countryside tea garden famous for its tea and cake.

Located on what is today one of London’s most filthy traffic junctions where the Euston, Tottenham Court and Hampstead Roads meet, this public house was known for its quiet orchards of wild fruit trees.

Its reputation declined as building developments encroached, with Larwood reporting the arrival of ‘highwaymen, footpads, pickpockets, and low women’. By the early 19th century the gardens were surrounded by houses notorious as hang-outs for prostitutes and criminals. The public house was subsequently closed by magistrates although it reopened as a tavern for a short time in 1813.

Agar Town

King’s Cross

CHARLES DICKENS DESCRIBED THE SLUM that grew up here from 1840 as ‘a suburban Connemara ... wretched hovels, the doors blocked up with mud, heaps of ash, oyster shells and decayed vegetables, the stench on a rainy morning is enough to knock down a bullock’.

The 72-acre site was previously the property of William Agar, a notorious litigant whose complaints even forced a change of direction in the intended route of the Regent’s Canal.

After Agar’s death in 1838, the shanty town in King’s Cross emerged when his widow sub-let the land. In 1851 one W M Thomas, a visitor to London, described his journey through the area: ‘The footpath, gradually narrowing, merged at length in the bog of the road. I hesitated; but to turn back was almost as dangerous as to go on. I thought, too, of the possibility of my wandering through the labyrinth of rows and crescents until I should be benighted; and the idea of a night in Agar Town, without a single lamp to guide my footsteps, emboldened me to proceed. Plunging at once into the mud, and hopping in the manner of a kangaroo – so as not to allow myself time to sink and disappear altogether – I found myself, at length, once more in the King’s Road.’

Among the slum’s most famous residents was the boxer Tom Sawyer, while the music hall star Dan Leno was born here in December 1860. The Midlands Railway Company bought Agar Town in 1866 and demolished it to make way for the railways. Such was the area’s poor reputation that there was little protest, even though its residents received no compensation. Today its name lives on in Agar Grove, a street running along the old slum’s northern boundary.

Alhambra

Leicester Square

BUILT IN A BROADLY MOORISH STYLE WITH TWO minarets, the Alhambra had a variety of different names and purposes. Originally opened in 1854 as the Royal Panopticon of Arts and Science, it boasted a huge hall, hydraulic lift, lecture theatre and 97ft-high fountain.

This initial venture was a failure and in 1856 its exhibits, displaying scientific wonders of the age, were sold off for a mere £8,000 – 10 per cent of what it cost to build.

Two years later the building reopened as a circus and from 1861 served as a music hall. Featured performers included Charles Blondin, who had recently tightrope-walked across Niagara Falls, and Jules Léotard, whose performances inspired the song ‘The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze’ (and after whom the tight-fitting one-piece garment is named). However, the Alhambra lost its entertainment licence in 1870 after hosting the first London performance of the Can-Can, during which the dancer ‘Wiry Sal’ lifted her foot ‘higher than her head several times towards the audience and had been much applauded’.

For the next decade it staged plays and promenade concerts before burning down in 1883. The following year it returned as a music hall and became a venue for ballet in 1919. The theatre was demolished in 1936 and where it once stood, facing into Leicester Square, is now an Odeon cinema. The Alhambra name does live on in Alhambra House on nearby Charing Cross Road, though rather than a palace of entertainment it is a somewhat miserable black marble-fronted building housing offices and a bank.

Alsatia

Temple

THE NAME ALSATIA DERIVES FROM THE LONG-disputed Alsace region on the French–German border that was historically outside normal legislative jurisdiction.

In London, Alsatia covers the area formerly occupied by London’s Whitefriars monastery, which is commemorated in an eponymous street that runs south from Fleet Street towards the River Thames.

After he dissolved the religious orders, Henry VIII parcelled out monastic lands to his favourites and so Alsatia was given to his physician, Doctor Butts. The area soon deteriorated into a maze of alleyways and squalid housing. Yet the idea of medieval religious sanctuary lived on in the area and from the 15th until the 17th century, the population defended itself against any bailiff or city official who tried to enter the area to arrest any of its inhabitants. However, by Elizabeth I’s time attempts were being made to clean up the area, as the State Papers record:

‘Item. These gates shalbe orderly shutt and opened at convenient times, and porters appointed for the same. Also, a scavenger to keep the precincte clean.

Item. Tipling houses shalbe bound for good order.

Item. Searches to be made by the constables, with the assistance of the inhabitants, at the commandmente of the justices.

Item. The poore within the precincte shalbe provyded for by the inhabitantes of the same.

Item. In tyme of plague, good order shalbe taken for the restrainte of the same.

Item. Lanterne and light to be mainteined duringe winter time.’

But these attempts had little or no effect and, surprisingly, the area’s liberties where enshrined in 1608 when James I granted it a charter.

It was once said of Alsatia that ‘the dregs of the age that was indeed full of dregs, vatted in that disreputabl

e sanctuary east of the Temple’. It was immortalised in two major literary works, Thomas Shadwell’s The Squire of Alsatia and Sir Walter Scott’s The Fortunes of Nigel, both of which drew vivid pictures of this ramshackle kingdom where people defended their liberties at all costs. Shadwell, for instance, depicted the following scene:

‘An arrest! An arrest!’ and in a moment they are ‘up in the Friars,’ with a cry of ‘fall on.’ The skulking debtors scuttle into their burrows, the bullies fling down cup and can, lug out their rusty blades, and rush into the mêlée. From every den and crib red-faced, bloated women hurry with fire-forks, spits, cudgels, pokers, and shovels. They’re ‘up in the Friars,’ with a vengeance!

In 1678 an Act of Parliament abolished the liberties of Alsatia and several other areas in the city, including The Minories, Salisbury Court, Mitre Court, Baldwins Gardens and Stepney. In 1723 London’s last two sanctuaries – at The Mint in Southwark and The Savoy – were finally abolished. However, the spirit of lawless autonomy lived on in many of these areas for years to come and grew elsewhere, as in the notorious ‘Rookeries’ that survived until the late Victorian era.

Archery

IN 1369 AN ACT OF PARLIAMENT DECREED that Londoners must practise archery and ‘that everyone of the said city of London strong of body, at leisure times and on holidays, use in their recreations bows and arrows’.

Despite the decline of the longbow as a potent military weapon over the preceeding 300 years, both Henry VIII and Elizabeth I tried to re-establish the practice. In 1627 archery regiments were formed by the City of London and practised annually in Finsbury, St George’s Fields and Moorfields. But towards the end of the 18th century urban encroachment forced the archers further away, with the Royal Toxophilite Society (founded 1781) eventually being driven to move from its Regent’s Park home to Buckinghamshire. Several parts of London maintain an association with the activity, such as the Archery Tavern, Bayswater, and Newington Butts at the Elephant and Castle.

Lost London

Lost London