- Home

- Richard Guard

Lost London Page 2

Lost London Read online

Page 2

Astley’s

Westminster Bridge Road

ORIGINALLY CALLED ROYAL GROVE, ASTLEY’S WAS London’s first circus. It was opened by a former cavalry officer, Philip Astley, who received a licence for his enterprise after he used his Herculean proportions to help George III subdue a runaway horse.

When his original site burned down in 1794, he rebuilt it as Astley’s Amphitheatre. Shows often featured clowns, acrobats and conjurers, and there were vast spectaculars featuring, for instance, ‘several hundred performers and fifty-two horses, two lions, kangaroos, pelicans, reindeer and a chamois’. Other entertainments included sword fights and exotic melodramas. The venue, though, was plagued by fires and had to be rebuilt in 1803, 1841 and 1862, when it reopened as the New Westminster Theatre. It was finally demolished in 1893. Charles Dickens was an avid Astley’s fan as both a child and adult, writing of it fondly in Sketches by Boz.

Atmospheric Railway

South East London

1845 SAW THE OPENING OF A REMARKABLE and revolutionary form of railway transport, powered not by steam but by compressed air.

Designed in Southwark by Samuel Clegg and the Samuda brothers, a line ran from Forest Hill to West Croydon with carriages driven by a piston connected to a pipe running between the rails.

A pumping station at either end of the track provided the air. With the trains unable to pass over the tracks of the regular railway at Norwood, Clegg and the Samudas built the world’s first railway flyover, which is still in use today.

The system was plagued by technical difficulties, mainly due to metal corrosion and wear and tear on leather seals. Indeed, passengers were frequently forced to push trains between stations when the pressure failed. Another major problem stemmed from the quietness of the trains, which somewhat perversely unnerved passengers.

By 1846 the cost of breakdowns and repairs forced the London and Croydon Railway Company to abandon its experiment and turn to the more reliable power of steam. But this wasn’t the end of atmospheric and pneumatic transport in London. In 1863 the Post Office built two tunnels out of Euston Station, one running half a mile to a sorting office and the other to St Paul’s in the City. Using pneumatic trains, the journey to St Paul’s took a mere nine minutes. The route ran until 1874 but high costs forced its closure. When the Tube system was first conceived, pneumatic power was again considered, and construction of such a line between Whitehall and Waterloo even got under way until a financial crisis in 1866 halted work that was never restarted.

Barbican

EC2

NAMED AFTER THE OUTER FORTIFICATIONS of the city, the original Barbican was most likely a watch-tower, which the great historian of London, John Stow, said was pulled down in the reign of Henry III. In the 16th and 17th centuries the area became well known for its market in new and used clothes.

Much of the locality was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 and was again devastated in the Blitz during the Second World War, when thirty-two acres were completely razed. Six major historic streets and numerous other courts and alley-ways were lost forever in the bombing. Amongst them were Jewin Cresent and Jewin Street, which had been the site of a Jewish enclave and burial ground until the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290.

John Milton was a resident here when he wrote Paradise Lost, while Redcross Street was formerly the home of the Abbot of Ramsey (as well as the site of a red cross that was still standing in the 16th century during Stow’s lifetime). Other places of interest included Paper Street, replete with warehouses for paper, and Silver Street, a hub for the city’s silversmiths. Elsewhere, Australia Avenue, built relatively recently in 1894 between Barbican and Jewin Crescent, was much used by those active in Antipodean trade. However, such was the destruction wrought between 1939 and 1945 that it was decided to rebuild the entire area on a new plan, creating the Barbican Centre that we have today, the largest multi-arts venue in Europe.

Bartholomew Fair

Smithfield

OF ALL THE GREAT CITY FAIRS, Bartholomew Fair was the oldest and most famous. It was held at West Smithfield, the site of modern-day Smithfield Market.

It was first celebrated in 1133 when Rahere, the founder of the local priory, was granted a charter to raise money for a new hospital, the now famous St Bartholomew. For the next 400 years Bartholomew was the primary cloth fair in the country, held over three days from each 24th August, the feast day of St Bartholomew. It was traditionally opened by the Lord Mayor, who would ride from the Guildhall to Smithfield to read the opening proclamation at the Fair’s entrance – having stopped on his way for a jug of wine spiced with nutmeg and sugar supplied by the keeper of Newgate. In 1688, one unfortunate Mayor, Sir John Shorter, closed his tankard lid with such violence that his horse bolted, dismounting the venerable gent, who died of his injuries the next day.

The mood of the event began to change at the beginning of the 17th century, when the city’s cloth dealers began to explore national and international markets outside of London. The fair evolved instead into an opportunity for general merriment and over the next century became increasingly rowdy, now less a trade fair than a joyous celebration and public holiday, complete with plays, puppet shows, freak shows and exotic animals. Samuel Pepys wrote of the experience in his diary:

Thence away by coach to Bartholomew Fayre, with my wife, and showed her the monkeys dancing on the ropes, which was strange, but such dirty sport that I was not pleased with it. There was also a horse with hoofs like rams hornes, a goose with four feet, and a cock with three. Thence to another place, and we saw a poor fellow, whose legs were tied behind his back, dance upon his hands with his arse above his head, and also dance upon his crutches, without any legs upon the ground to help him, which he did with that pain that I was sorry to see it, and did pity him and give him money after he had done.

The year 1817 witnessed the appearance of Toby, a ‘real learned pig’ who, with twenty handkerchiefs covering his eyes, could tell the time to the minute and pick out cards from a pack. Meanwhile, Thomas Horne recorded seeing ‘four lively little crocodiles hatched from eggs at Peckham by steam’. But the drunken debauchery among visitors to the fair began to irk the city authorities. In 1801, for instance, a gang of thieves surrounded a respectable lady and tore the clothes from her back, while a year later random victims were attacked with cudgels and several windows were broken.

In 1815 alone the Guildhall heard forty-five cases of felony, misdemeanor and assault committed at Bartholomew and so the city embarked on a concerted effort to clean up the event. Many of the raucous shows and booths were moved to Islington and by 1840 only the animal shows still remained. By 1849 the fair amounted to little more than a few gingerbread stalls and in 1850, Lord Mayor Musgrove turned up for the opening ceremony to find no one there. Five years later even this 700-year-old ceremony was abandoned and London’s greatest fair was consigned to history.

Baynard’s Castle

Blackfriars

THE NAME REFERS TO TWO CASTLES THAT WERE in roughly the same area, east of the current Blackfriars Bridge. The first was a Norman-built castle demolished by King John in 1213 after he was jilted by its owner’s daughter.

Legend tells that the King took a fancy to Matilda Fitzwater (known as ‘the Fair’), daughter of the master of the house, but she would not consent to become his mistress. Her father fled and she was carried off to the Tower of London, only to be poisoned with powder sprinkled on to her poached egg.

The second castle was built fifty years later and about a hundred yards east of the original. (Some other land from the Fitzwater estate was gifted to the Dominican order of monks, giving rise to the area becoming known as Blackfriars). The new fortress eventually became a royal household, with Edward IV crowned there in 1452, followed by both Lady Jane Grey and Mary I in 1553. During the reign of Henry VIII it served as the home to three of his wives – Katherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn and Anne of Cleves.

Pepys wrote that Charles II stayed her

e in 1660 but the building, reportedly ‘one of the most interesting in London’, was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 and never rebuilt, although one tower remained until 1720. Excavation of the site in the 1970s revealed that much of the castle’s outer limits were built upon the remains of a Roman wall that ran along the river bank, the existence of which had been disputed for many years.

Bedlam, or St Bethlehem’s Hospital

Liverpool Street

THERE HAVE BEEN THREE SEPARATE SITES FOR this most famous of mental hospitals. The first was at Bishopsgate, on the site of modern-day Liverpool Street railway station. Established in 1329 as a regular hospital run by the Priory of St Mary Bethlehem, by 1377 it was taking in ‘distracted’ patients.

Treatment was unsophisticated and often cruel, with inmates commonly chained, beaten, whipped and ducked.

With the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII, ‘Bedlam’ fell under the control of Bridewell, a local prison. The already deplorable conditions for inmates continued to deteriorate. Eventually a grand new building was opened at Moorfields around 1675–76, designed by Robert Hook and with a front entrance adorned by two famous sculptures of Madness and Melancholy by Caius Cibber. These figures are all that remains of the second Bedlam and now reside in the Victoria & Albert Museum. A version of them can also be seen in the chilling final plate of Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress.

Much of the Hospital’s income was derived from admitting visitors to view the ‘idiots’. It became a popular holiday destination for many city dwellers over the next 100 years, until the practise was outlawed in 1770 as it ‘tended to disturb the equilibrium of the patients’. From then on, visitor numbers were controlled and sightseers had to buy a ticket in advance to get in.

By 1800, Hook’s great building, once described as a match for the Tuileries Palace in Paris, was starting to decay, with the blame laid on cheap materials. So a new site for the hospital was found in St George’s Fields, Southwark (above). Patients were moved there in 1815 and conditions gradually improved. In 1851 a resident doctor was appointed, although the habit of viewing inmates remained ever popular. A balcony at the Grand Union pub on Brook Street was specially built to overlook the gardens and is still there to this day. The last patients left the institution in 1930 and the building was reopened in 1936 as the Imperial War Museum.

Bishopgate

ONE OF THE EIGHT ORIGINAL GATES TO THE city, standing at Bishopsgate and Camomile Street.

The others included Aldgate, Moorgate, Cripplegate, Aldersgate, Newgate and Ludgate – all of which were demolished to increase the flow of traffic in the period 1760–61. The only one that remains is Temple Bar.

Bon Marché

Brixton

JAMES SMITH, A PRINTER FROM TOOTING, WON a fortune at Newmarket races in 1877 and proceeded to reinvent himself as Rosebery Smith.

With his newfound riches he opened the city’s first purpose-built department store. Why he chose 442–444 Brixton Road is anyone’s guess, but the name he decided upon was Bon Marché, after the famous store in Paris. Unfortunately, Smith was no great businessman and he soon went bankrupt. The store, however, went on for almost another 100 years, declining only after the Second World War. It briefly became the Brixton Fair before closing for good in the 1970s.

Bridewell

Banks of River Fleet

A ROYAL PALACE BUILT BETWEEN 1515 and 1520 on the western bank of the Fleet River, it was mainly used for entertaining visiting foreign dignitaries, most notably the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles v. On a visit in 1522, he enjoyed tennis, feasts, music and pageants here.

Hans Holbein painted his famous The Ambassadors at the palace and it was also the site of the Papal Legatine inquiry into the marriage of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon. Bridewell provided the backdrop for Katherine’s famous and noble speech in which she defended her position:

This 20 years or more I have been your true wife and by me ye have had divers children, although it hath pleased God to call them from this world, which hath been no default in me ... And when ye had me at first, I take God to my judge, I was a true maid, without touch of man. And whether this be true or no, I put it to your conscience ... Therefore, I humbly require you to spare me the extremity of this new court ... And if ye will not, to God I commit my cause.

Perhaps because of the unfortunate events played out here, Henry’s son, Edward VI, gave up Bridewell Palace after being nagged to do so by Archbishop Ridley. In a sermon, Ridley had asked the King to provide a place for ‘the strumpet and the idle person, the rioter... and the vagabond’ and so Bridewell thenceforth became a house of correction for short-term prisoners. Floggings were held twice a week, and a ducking stool and stocks had been installed by 1638. Hogarth immortalized the place in plate 4 of The Harlot’s Progress, which shows the harlot beating hemp as a punishment.

Bridewell also took in a number of orphans and destitute children, known for the blue uniforms they wore. It became both a school and a prison and in 1700 was the first jail to appoint its own medical staff. The model was so successful that the regime was copied and the name came to be used at other institutions in the city at Westminster and Clerkenwell, as well as further afield in Norwich and Edinburgh. The original Bridewell was eventually closed in 1855 and its location is today the site of Unilever House.

Carlisle House

Soho Square

BUILT IN 1685 FOR THE SECOND EARL of Carlisle, this was a private home for many decades before hosting an upholstery company and then becoming the lodgings of the Neapolitan Ambassador.

In 1759 it was rented out to a Venetian society belle, Mrs Cornelys. A lady who scorned social mores, she converted the building into a venue for masquerades, card evenings and musical concerts, some of which were directed by the composer J S Bach. Increasingly risqué events led to the extravagant Mrs Cornelys being repeatedly fined for keeping a ‘disorderly house’.

Although initially massively popular, the venue started to decline with the opening of the Pantheon on Oxford Street in 1772. Desperate to retain the house’s reputation as the premier society venue, she undertook once again to refurbish it, even more grandiosely this time. The debts she incurred crippled her business and she was arrested and imprisoned in October 1772 at the King’s Bench Prison, where she died in 1797. Amongst her various claims to fame was that Casanova was the father of her daughter.

For several years the rooms continued as a house of entertainment but garnered a much less salubrious clientele. One foreign visitor described the guests thus: ‘The ladies were rigged in gaudy attire, attended by bucks, bloods and macaronis ...’ The house closed in 1781 and was demolished in 1791, the site redeveloped as St Patrick’s Catholic Church.

Charing Cross

ALSO KNOWN AS ELEANOR’S CROSS ERECTED BY Edward I, King of England (1272-1307) following the death of his wife of 46 years, Eleanor of Castille in 1290.

When she died, near Lincoln, her body was transported to Westminster, a journey that took twelve days. Edward had a memorial cross erected at every resting place of her funeral procession. The last at the village of Charing, a stopover between the City of London and Westminster.

Originally constructed of wood it was replaced by a cross of Caen stone, octagonal in shape, with smooth marble steps and decorated with eight statues. Removed by the Parliamentary Act of 1643, it was not actually taken away until 1647, the stone reputedly being used to pave Whitehall.

The cross built in the forecourt of Charing Cross Station is a Victorian replacement, 180 yards away from its former location now marked by a statue of Charles I on horseback looking down Whitehall. For many years this spot was used to measure distances from London, replacing St Paul’s, and prior to that the London Stone, the Roman mile-post in Cannon Street. London taxi drivers are required to know all the streets within a six-mile radius of Charing Cross, a principal that was instituted in 1865.

Chelsea Bun House

Pimlico

OPENIN

G IN THE EARLY 1700S IN JEW’S ROW (now Pimlico Road), this is where Chelsea buns were invented. In its day, the Bun House was hugely famous, prompting Jonathan Swift to celebrate the ‘Rrrrrrrare Chelsea buns’ after he visited in 1711.

Its proprietor, Richard Hand, decorated the interior with clocks and a collection of curious artefacts. The Bun House even found popularity among royalty, with both George II and George III, their wives and children all visiting.

So successful was the business that on Good Fridays, crowds of over 50,000 gathered outside the premises to purchase its products. The crush was such that in 1793 Mrs Hand issued a notice that ‘respectfully informed her friends and customers that in consequence of the great concourse of people Good Friday last by which her neighbours have been much alarmed and annoyed ... she is determined, though much to her loss, not to sell Cross Buns on that day’.

In 1804 the closure of the nearby Ranelagh Gardens had a profound effect on trade and the business began to decline. Yet even so, on Good Friday 1839 the House sold a staggering 240,000 buns. Nonetheless, the building was demolished later the same year.

Chippendale’s Workshop

Covent Garden

IN DECEMBER 1753, THE RENOWNED cabinet-maker, Thomas Chippendale, leased the building at 60–61 St Martin’s Lane in Covent Garden. It was from here that he published the legendary Gentlemen and Cabinet Maker’s Directory.

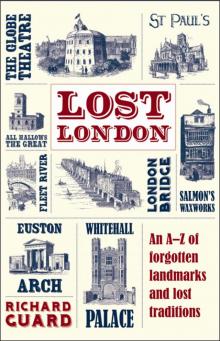

Lost London

Lost London